Indeed, the proposed guidelines steer doctors away from using opioids as a first-line therapy for many common acute pain conditions - among them, lower back pain, musculoskeletal injuries and pain related to minor surgeries. "The CDC's changes are really an effort to ameliorate that without losing track of the fact that these medicines were vastly overused and oversold for a period of decades," he says.

Kertesz believes that is a much needed recognition of how the previous guidelines were misapplied, especially to patients already on a stable regimen of opioids for chronic pain. The authors state upfront that it's not "intended to be applied as inflexible standards of care" or as "law, regulation or policy that dictates clinical practice." The new guidelines also emphasize that clinicians should use their own judgment in deciding what will be a safe and effective dose for each patient. With the original guidelines, "it turned out that insurance companies and regulators seized on those numbers as simple tools to force changes to care that often were not safe for patients," he says. Stefan Kertesz, a professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The topline recommendations - often the takeaways for clinicians and policymakers - no longer include specific limits on the dose and duration of an opioid prescription that a patient can take. The new proposed guidelines - a sprawling, 200-page document - continue to advise against using opioids for pain when possible and to take a cautious approach when it's necessary, given the risks of opioid misuse and overdose.īut there are some notable changes from the old guidance. And yet many others, including patients with chronic pain, argue that the guidance is still flawed - with the potential of being misinterpreted and misapplied. Some experts see the proposed changes as a promising step toward addressing the harms suffered by pain patients in the wake of the previous guidelines. The public comment period ends on Monday, and then the agency will weigh its final recommendations. This is why the agency's revised guidance is now under scrutiny. "It's a really tough situation out there." "I hear from patients every week and doctors just don't even want to see pain patients," she says. The restrictive climate around prescribing has persisted, says Cindy Steinberg, director of national policy and advocacy for the U.S. Many states adopted laws and regulations that set limits on prescribing, and health insurers also crafted policies to that effect.Īnd doctors grew wary of giving opioids at all, which often led to sudden disruptions of treatment, resulting in physical and mental agony, and even a heightened risk of suicide. That advice is widely blamed for leading to harmful consequences for patients with chronic pain.įederal officials have acknowledged their original guidance was often misapplied it was supposed to serve as a roadmap for clinicians navigating tricky decisions around opioids and pain - not as a rigid set of rules.īut the 2016 version was used as the basis for sweeping policy decisions, as lawmakers and health leaders struggled to contain the nation's overdose crisis.

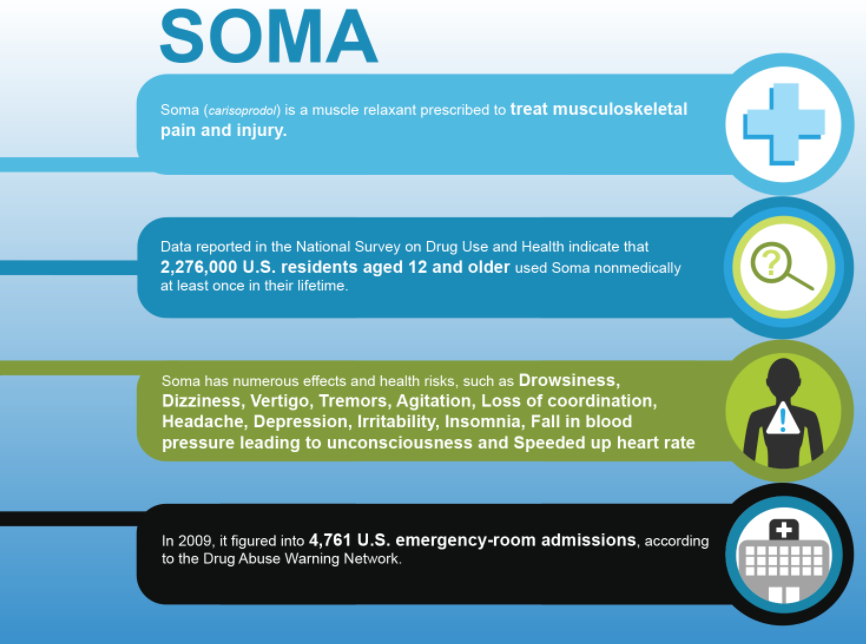

#Soma medication update#

Those guidelines – currently under review as a draft – will serve as an update to the agency's previous advice on opioids, issued in 2016. Doctors will soon have new guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on how and when to prescribe opioids for pain.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)